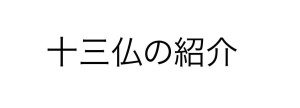

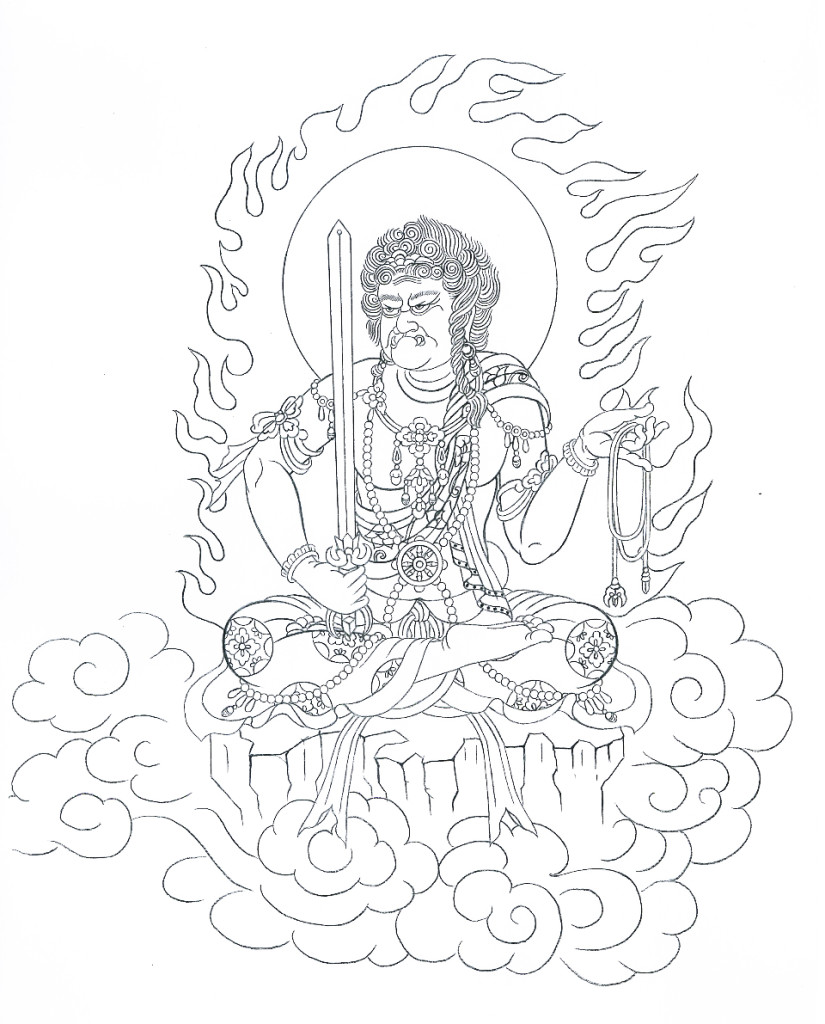

1. Fudō-Myō-ō 不動明王

Premortem date of worship: sixteenth day of the first month.

Postmortem date of worship: seven days after death.

Fudō Myō-ō, “The Immovable King of Light”, was first introduced to Japan by Kūkai (779-835), the founder of Shingon Buddhism. Fudō is a translation of the Sanskrit Acala, which means “not moving”. Although his immovability is often interpreted to represent fortitude and obstinacy (compounded by the rock by which he stands), the Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki suggested that it refers to the immovable intelligence of the mind remaining forever tranquil and yet mobile all the time.

Fudō Myō-ō, “The Immovable King of Light”, was first introduced to Japan by Kūkai (779-835), the founder of Shingon Buddhism. Fudō is a translation of the Sanskrit Acala, which means “not moving”. Although his immovability is often interpreted to represent fortitude and obstinacy (compounded by the rock by which he stands), the Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki suggested that it refers to the immovable intelligence of the mind remaining forever tranquil and yet mobile all the time.

His fearsome appearance belies his compassion for sentient beings: he uses the sword in his right hand to destroy evil desires, ignorance, pride; in his left hand he carries a binding rope to discipline the mind and draw beings in towards liberation. Surrounded by flames symbolizing the metaphysical knowledge which burns ignorance, he remains the deity most commonly invoked in the goma fire purification rituals performed in the esoteric sects. However, perhaps because of his lightning-like sword, he has also been the focal point of many mystical rain-making rituals.

Fudō is viewed to be an alter ego of Dainichi Nyorai so consequently he can often be seen standing in the vicinity of Dainichi in paintings and sculptures. Offerings are made to him on the seventh day after death in order that he will come to pacify the minds of the recently deceased.

2. Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来

Premortem date : twenty-ninth day of the second month.

Postmortem date: fourteen days after death.

Shaka is the Japanese name for Sakyamuni (Sage of the Shaka Clan), the historical Buddha on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. Born in present day Nepal in either the mid-6th or mid-5th century B.C., he left behind a life of privilege to become a mendicant ascetic at 29 years old, and 6 years later attained enlightenment, thereby becoming a Buddha or ‘enlightened one’.

It was originally deemed inappropriate to depict the actual form of the Buddha in human form, so instead he was represented by symbols such as the Wheel of the Law (Dharmacakra), the lotus flower, the conch shell and the Bodhi tree. The first anthropomorphic images started to appear in the Christian era, and it was said that the form of his body was borrowed from the wide breast and narrow waist of the lion and the head from the bull, while the eyes recall the lotus bud, the eyebrows the Indian bow, and the three folds of the neck the undulations of the conch shell.

Two of the most common hand gestures associated with Shaka are the “Fear not Mudra” (right hand held up), a gesture that symbolizes the granting of protection to Buddhist followers, and the “Exposition of the Dharma Mudra” (featured in the illustration) which is the mudra he used when preaching his first sermon after reaching enlightenment. Significantly, the hands are held in front of the heart in this mudra, symbolizing that the Buddha’s teachings come straight from the heart.

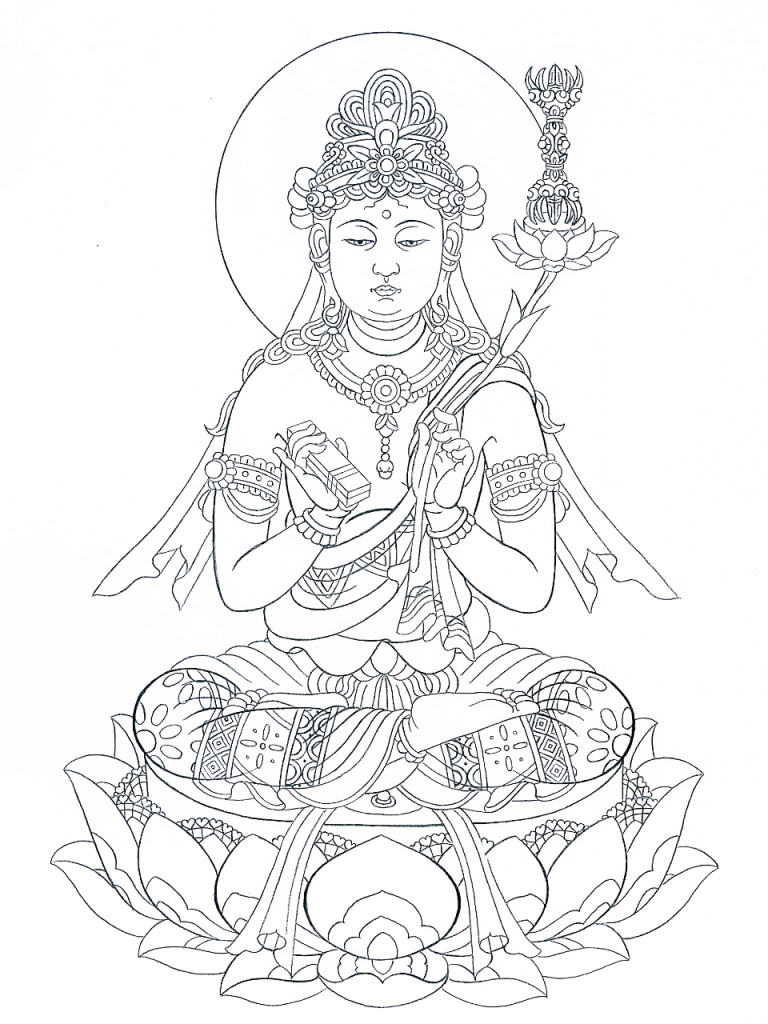

3. Monju-bosatsu 文殊菩薩

Premortem date: twenty-fifth day of the third month.

Postmortem date: twenty-one days after death.

Monju is a Bodhisattva of wisdom. Wisdom is a concept derived from prajnā, and can be broadly defined within Buddhism to refer to right cognition: the understanding of the absence of a permanent, abiding self in all things. He often carries a sword in his right hand to sever the roots of ignorance and aid all beings to awakening; in his left hand he either holds a scroll which represents the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (hannya kyō 般若経), or a lotus flower which symbolizes the pure, undefiled Buddha mind.

Monju is often depicted with five curls in his hair and there are also five syllables in his mantra if the honorific “On” is omitted. In specific relation to Monju, five represents the five wisdom peaks of Godaisan 五台山, his holy mountain in China, which to this day remains a popular place for Buddhist pilgrimages.

Monju and Fugen are often portrayed either side of Shaka in a grouping known as the Shaka trinity or triad (Shaka sanzon 釈迦三尊). Monju is usually positioned on the left side on top of a lion holding a sword—a style of Monju first introduced to Japan in the Heian era by the Tendai Buddhist monk Ennin. The word “arahashano” in Monju’s mantra “homage to arahashano” is the name of an Indian alphabet. Since Monju symbolizes both learning and transcendental wisdom, it is appropriate to his mantra.

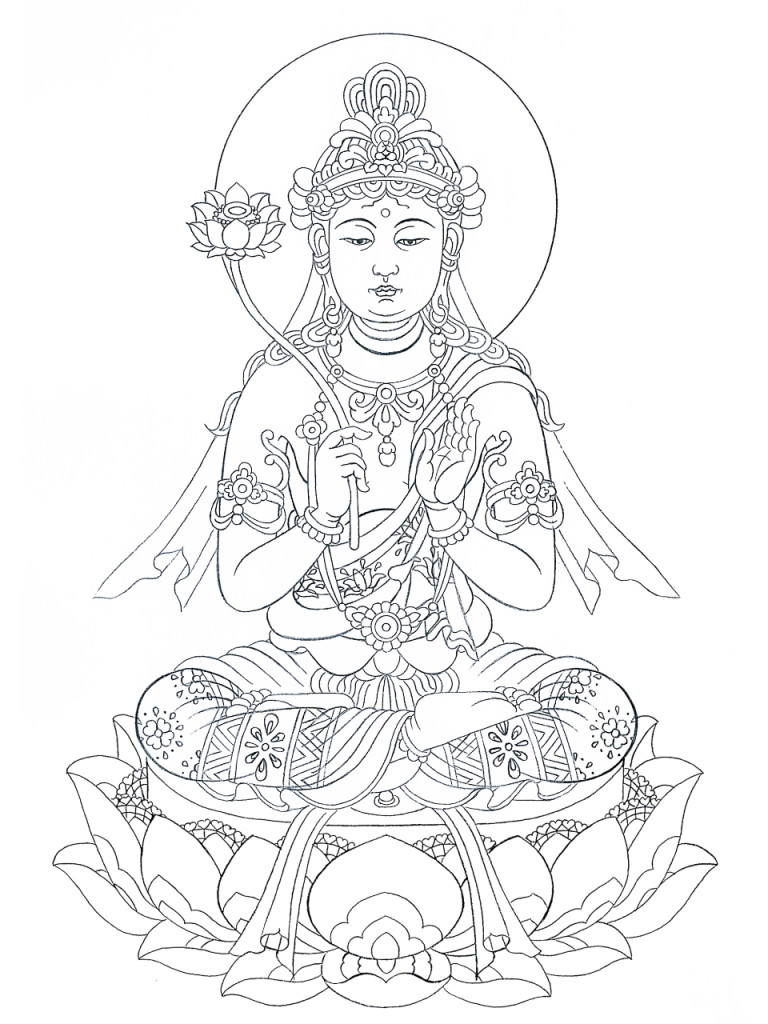

4. Fugen-bosatsu 普賢菩薩

Premortem date: fourteenth day of the fourth month.

Postmortem date: twenty-eight days after death.

Fugen represents the virtues of meditation and diligent practice. He is venerated for the ten vows or resolutions he took to obtain enlightenment which have become common practice in East Asian Buddhism. He is ordinarily portrayed sitting on top of a white elephant with six tusks. The elephant symbolises the strength of Buddhism to overcome all obstacles and the six tusks represent the six fields: sight, sound, scent, taste, touch and concepts (of the mind).

Though originally male, and often featuring a moustache, Fugen came to have a feminine appearance and represent the ideal of feminine beauty. He is often depicted alongside Monju, but whereas Monju is the patron of the transcendental wisdom gained at the end of one’s religious quest, Fugen is the patron of the religious quest itself.

He is portrayed in the Womb World Mandala holding a three-pronged vajra in his left hand which rests upon a lotus flower. Within esoteric and other forms of tantric-based Buddhism, the vajra is often paired with the lotus as representing two aspects of a single (non-dual) reality. In other representations, Fugen is sometimes seen with both hands pressed together in prayer or with his right hand palm facing up with three fingers outstretched (see picture). The three fingers represent the three forms of conduct: thoughts, words and actions, each of which respectively form the “three mysteries” of esoteric Buddhism: Meditation, Mantra and Mudra.

5. Jizō-bosatsu 地蔵菩薩

Premortem date: twenty-fourth day of the fifth month.

Postmortem date: thirty five days after death.

The much-loved Jizō rose to prominence in Japan at the end of the Heian period and he is widely regarded as a Bodhisattva of compassion. However, his role has changed considerably through the ages: from saviour and guide, to protector of travellers and women in childbirth. These days, he is most widely seen as the protector of children and it is common to see statues of Jizō at temples adorned with red bibs and caps which were said to have been worn by children in earlier times. Women who have had a miscarriage, stillbirth or abortion, will often visit temples and pay their respects to Jizō in a kind of fetus memorial service known as mizuko kuyō 水子供養.

Jizō has a number of feminine traits, and in a previous existence he was said to have been a woman. He holds a wish giving pearl in his left hand that represents the effulgence of Buddhist doctrine, and carries a staff with six rings that symbolize the six realms of reincarnation. Groups of six Jizō statues (see below) are commonly found outside Buddhist temples or placed at busy intersections for the protection of travelers.

6. Miroku-bosatsu 弥勒菩薩

Premortem date: fifteenth day of the sixth month.

Postmortem date: forty-two days after death.

The cult of Miroku entered Japan in the early sixth century and developed into two basic motifs: a motif of ascent (jōsho 上生) and a motif of descent (geshō 下生). In the former, Miroku is believed to be residing in Tusita heaven (tosotsuten 兜率天) a place of rebirth for devotees who have acquired enough merit. In the descent motif, Miroku is the messianic Buddha of the future, who will one day come to earth to put an end to the sufferings of the virtuous and restore true religion. It is a commonly held belief by the followers of Shingon Buddhism that their leader Kūkai did not die and merely entered a state of suspended life at Mt Kōya where he awaits Miroku’s descent.

The earliest depictions of Miroku such as the wood carving displayed at Chūgūji (see p.106), show a relaxed, contemplative posture implying both the ease and elegance of Miroku’s paradise and his pondering how to save all the beings in the world. In other representations, Miroku is shown seated cross-legged holding a lotus flower in his right hand with a small vase of water resting upon it containing an elixir of wisdom.

Some scholars have suggested that Miroku’s messianic qualities contradict the need for self-effort to attain enlightenment, stressed by the Buddha himself. However, if we view Miroku’s paradise as the emanation of a world after all human beings have fully integrated the teachings of the Buddha into their lives, there is no discernible contradiction.

7. Yakushi Nyorai 薬師如来

Premortem date: eighth day of the seventh month.

Postmortem date: forty-nine days after death.

Yakushi is the medicine Buddha, the doctor of souls and bodies. He holds a pot of medicine in one hand, to heal the sicknesses of body and mind, and he is sometimes flanked either side by the Bodhisattvas of the sun and moon (Nikkō and Gakkō), perhaps because the early practice of medicine was associated with solar and lunar principles. He is typically shown seated with the palm of his right hand raised in the “Fear not Mudra” but on rare occasions he may be observed with both hands lying in his lap, thumbs together, palms up supporting the pot of medicine. The pot contains a balm to cure the blindness of ignorance and awaken the True Eye of Dharma.

Yakushi assumes the seventh position in the Thirteen Buddha Rites; a number which has been associated with him since the medieval period as he was believed to manifest in seven forms (shichibutsu yakushi 七仏薬師). He is also affiliated with the number twelve for the twelve vows he made as a Bodhisattva, and upon the fulfillment of these vows he became the Lord of the Eastern Paradise of Pure Lapis Lazuli (jōruri 浄瑠璃). Yakushi and his scriptures are protected by Twelve Heavenly Generals (jūnishinshō 十二神将). These twelve protective deities became associated with the twelve animals of the Chinese Zodiac.

8. Kannon-bosatsu 観音菩薩

Premortem date: eighteenth day of the eighth month

Postmortem date: one hundred days after death.

Kannon (the one who sees/hears all), also referred to as Kanzeon 観世音, is best conceptualized as the Bodhisattva of mercy. Understood to protect living beings with loving compassion, Kannon remains one of the most popular Buddhist deities in Japan. The faithful are promised that Kannon will shatter the sword of the executioner, grant the birth of sons and enable someone who has fallen from a high cliff to hang suspended in midair.

Kannon presides over an island mountain paradise called Fudaraku (補陀落) considered to be a Pure Land accessible from the Earthly Realm (the location is most commonly placed near the southern tip of India which suggests a south Indian origin for this deity). Vowing to continually work for the salvation of sentient beings, Kannon is said to appear in thirty-three different forms. The deity also has a further six esoteric or tantric forms, one being the six-armed Nyoirin Kannon whose duty is to save all sentient beings trapped in the Six Realms of Reincarnation.

Originally male in appearance, Kannon is now often portrayed as a female in Japan assuming the archetypal attributes of the divine mother goddess. Most commonly, Kannon is represented wearing a crown and holding a lotus or a water vase. The eighteenth day of each month is considered Kannon’s holy day (ennichi 縁日), so fittingly the premortem rite date for Kannon is the eighteenth of August.

9. Seishi-bosatsu 勢至菩薩

Premortem date: twenty-third day of the ninth month.

Postmortem date: one year after death.

Seishi bosatsu, also known as Dai (Great) Seishi meaning “he who has attained great strength”, is one of the lesser well-known and worshipped deities of the Thirteen Buddhas. It is very rare to find him depicted alone in Buddhist art and he is mostly only recognized as part of the Amida triad where he is often positioned on the right side of Amida with his hands pressed together in front of his chest in the “praying hands” pose.

The late esoteric philosopher Manly.P.Hall explained the Amida trinity as an allegory of the spiritual, mental and generative powers of the Sun; represented anatomically in the heart, mind and reproductive system. According to his interpretation, Seishi (the physical aspect) and Kannon (the mental aspect) become reflexes or expressions of Amida, the spiritual solar logos. A more traditional interpretation suggests Seishi represents the masculine attribute of knowledge or wisdom working in contradistinction to the feminine grace of Kannon while Amida stands for the Buddha nature in sentient beings.

In memorial services, offerings are made to Seishi one year after death. As this may be a time when the bereaved families diligence to perform the rites has subsided, the light and wisdom of Seishi (symbolized by his crown ornamented with a small vase of water) is believed to rejuvenate their compassion.

10. Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来

Premortem date: fifteenth day of the tenth month.

Postmortem date: three years after death.

Amida, the Buddha of “Immeasurable Light”, is the central deity of the Pure Land sects which came to prominence in Japan in the Kamakura era and remain some of the nation’s largest and most popular. Amida faith is predominantly concerned with the after-life, and those who call his name and meditate on his characteristics are said to be reborn in the Western Paradise of Ultimate Bliss (gokuraku jyōdo 極楽浄土) where Amida resides. This doctrine was denounced vociferously by influential Buddhist figures such as Nichiren (1222-1282) and Hakuin (1686-1768), who stressed that the Pure Land existed within one’s own mind and could only be discovered through diligent practice and meditation.

Welcoming approach (Raigō 来迎) paintings of Amida descending from paradise on a purple cloud to receive a believer at the time of death are renowned in Buddhist art. In other representations, Amida may be displayed seated or standing, paired with another Buddha or as the central part of a triad. He holds no defining attributes but is usually portrayed performing one of three main mudras. The Meditation Mudra (zenjōin 禅定印 ),where his hands rest on his lap, is most famously displayed in the large statue of Amida in Kamakura. The Mudra of the Exposition of the Dharma (Seppōin 説法印) shows both hands pointing upwards, thumb and forefingers pressed together. Finally, the Welcoming Mudra (Raigōin 来迎印), has the right hand raised, left hand lowered with the thumb touching one of three fingers.

11. Ashuku Nyorai 阿閦如来

Premortem date: fifteenth day of the eleventh month.

Postmortem date: seven years after death.

Ashuku is the Buddha of the Pure Land in the East: Zenke 善快— the Land of Great Pleasure. His Japanese name is a translation of the Sanskrit Aksobhya (the immovable or unshakeable one) and refers to his even temperament. According to Buddhist scripture, Ashuku made a vow to generate no thoughts of anger or malice until he attained enlightenment. He has a high status within esoteric sects as one of the four Buddhas that guard Dainichi Nyorai in the perfected body assembly (jōjine 成身会) of the Diamond World Mandala. This mandala is a central component of the esoteric Buddhist teachings, and it is perhaps best explained as a kind of encoded map used in conjunction with the Womb World Mandala to navigate the practitioner towards union with cosmological reality.

Ashuku’s iconographical characteristic is the Earth-Touching Mudra (shokuchi-in 触地印) which symbolizes his spiritual immovability. His left hand either lies in his lap clenched to form the “adamantine fist” (kongōken 金剛拳), or it may hold a corner of his robe. The latter gesture signifies his determination to support and encourage others to attain enlightenment.

12. Dainichi Nyorai 大日如来

Premortem date: twenty-eighth day of the eleventh month.

Postmortem date: thirteen years after death.

Dainichi Nyorai, the primordial cosmic Buddha of the Shingon sect, represents the life energy of the universe: the source from which all the other Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are brought into being. The Shingon scholar Taiko Yamazaki stated that he might have originated from the deity known in the Vedas as Asura, which in turn seems to be related to the Zoroastrian Ahura Mazda, god of light. However, it is important to point out that unlike other solar deities, Dainichi represents the inborn life-energy of the universe, and is therefore the Sun that never sets.

He is often portrayed clasping the forefinger of his left hand with his right, in a mudra known as the Wisdom Fist (chiken-in 智拳印). The five fingers of the right hand represent the five material elements (earth, water, fire, wind, space) and the index finger of the left hand represents the sixth element: mind or consciousness. According to Shingon cosmology, just as human beings consist of five material elements and a spiritual element (mind), so too does Dainichi consist of an enlightened mind and body. The interlinked hands demonstrate the interpenetrability of the Diamond and Womb World Mandalas and their unification signifies the inseparability of the microcosm and the macrocosm.

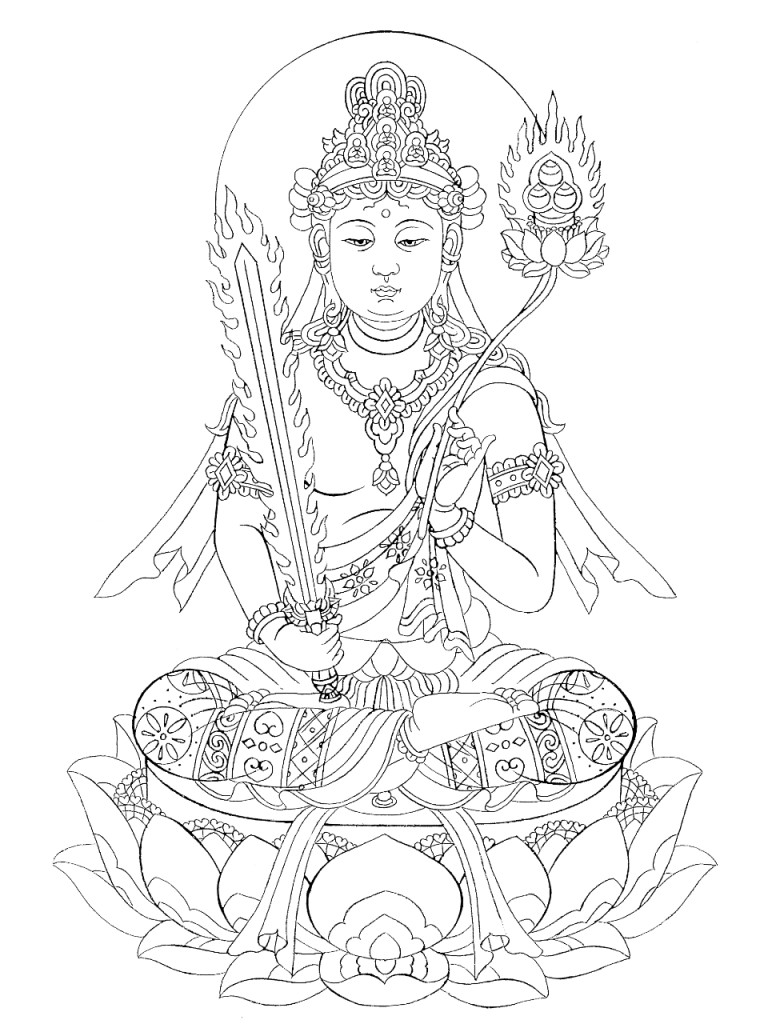

13. Kokūzō-bosatsu 虚空蔵菩薩

Premortem date: thirteenth day of the twelfth month.

Postmortem date: thirty-three years after death.

The thirteenth and final deity is the Bodhisattva Kokūzō, the “Womb of Emptiness” or “Storehouse of Wisdom”, who symbolises unlimited wisdom and compassion and is believed to be able to grant all wishes. More esoterically, he represents the fifth element: ether or space—the highest of the first five elements (See DeVisser, p.10). He also represents the planet Venus in the Shingon ritual the gumonjihō 求聞持法, a prolonged mantra recital and meditation practice believed to bestow the devoted practitioner with the boon of supernatural memory.

Kokūzō is typically shown holding a sword in his right hand, and a lotus flower in his left on which is placed a precious jewel. As the thirteenth deity, Kokūzō is intimately connected with the number thirteen. His premortem date is the thirteenth of the twelfth month and on the Japanese island of Honshu, children who are thirteen years of age pay homage to Kokūzō in the hopes of becoming more intelligent. In postmortem rituals, Kokūzō marks the thirty-third year of death. The number thirty-three signifies a stage of ascension or transformation and in the context of the Thirteen Buddha rites it marks the point in time when the deceased attains Nirvanic salvation or reincarnation. Formal offerings and services from surviving family members are no longer required after the thirty-third year and the Thirteen Buddha Rites come to their completion.