PART ONE: THE THIRTEEN BUDDHA RITES IN SCRIPTURE

Chapter 1: Seven Seventh-day Rites

To understand how the Thirteen Buddha Rites came to be, it is important to try to locate their place within the larger historical development of Japanese premortem and postmortem rituals. Surviving written documents from the early Heian period record postmortem rituals conducted by the elite members of Japanese society as far back as the eighth century. It was believed that these rituals, if done properly, enabled the living to transfer merit to restore the karmic balance of the soul as it passed through the crucial forty-nine day period after death. I begin by drawing from some of the earliest written records of these rituals found in courtiers diaries commonly referred to as kanbun nikki 漢文日記. Here we find written evidence that these forty-nine days— divided into seven periods of seven days— were associated with various Buddhist deities for both postmortem and premortem rituals known as the “seven seventh-day rites”.

Chapter 2: The Scripture on the Ten Kings

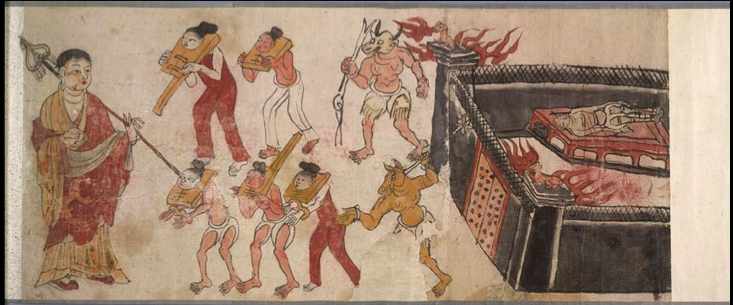

Despite the existence of seventh seventh day rites in medieval Japan, most scholarship on the Thirteen Buddha Rites attributes their origin to the Chinese belief in the Ten Kings of Hell that was brought to Japan around the twelfth century. I investigate this belief in chapter two and discuss how The Scripture on the Ten Kings of Hell redefined the afterlife as a kind of bureaucratic purgatory

Chapter 3: The Scripture on Jizō and the Ten Kings

In this chapter, we shall see how the Bodhisattva Jizō’s identification as the alter ego of Enma ō (the judge of the dead) made him an essential element in the interpretation of the Ten Kings as manifestations of Buddhist deities, made explicit in The Scripture on Jizō and the Ten Kings.

Chapter 4: Kōbō Daishi Gyakushu nikkinokoto

Chapter 4 focuses on an important apocryphal scripture known as the Kōbō Daishi Gyakushu nikkinokoto 弘法大師逆修日記事. This provided the template for the Thirteen Buddha Rites by extending the period for postmortem rites to thirty-three years after death, and standardizing the selection, order and number of Buddhist deities, which had hitherto been quite varied. It was also one of the earliest written records to include dates for premortem worship, and I shall reveal how the selection of these dates were influenced by some obscure beliefs and traditions known as the sanjūnichi hibutsu 三十日密仏 and the jūsainichi shinkō 十斎日信仰.

Chapter 5: Esoteric Interpretations

Due to the lack of written sources available, researchers have only been able to speculate theories about the reasons why three more deities were added to the Ten Kings and the period of worship extended from three to thirty-three years after death. This has led to a number of interesting theories on the importance of some of the numerological correspondences of the Thirteen Buddha Rites, and some intriguing ideas concerning the esoteric meaning of the rites which I discuss in detail in this chapter.

PART TWO: ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF THIRTEEN BUDDHA RITES

Part two of the book focuses on the archaeological evidence of stone memorials and sites related to Thirteen Buddha rituals and worship. I have chosen a selection of monuments and steles that illustrate a transitional period between the worship of the Ten Kings and the Thirteen Buddhas. I demonstrate how some of these monuments predate the earliest written documents on the Thirteen Buddha Rites, and explain what this tells us about their historical development.

Above: Hotsuki Rokumensekidō 保月六面石幢, Okayama Prefecture (Picture Kawai Tetsuo)

Above: Haguro jūsanbutsudō 羽黒十三仏堂, Chiba Prefecture (Picture Kawai Tetsuo).

Above: Jikōji 慈光寺, Saitama Prefecture (Picture Kawai Tesuo). Thirteen Sanskrit symbols of the Thirteen Buddhas adorn this stone stele.